Trans-Pacific space-age Wagner: Chen Shi-Zheng’s hybrid Ring cycle

by Anastasia

The countdown is on for Opera Australia’s futuristic East-meets-West Ring cycle. Postponed twice due to Covid, the epic Wagnerian creation – featuring sixteen hours of music over four nights – will finally open at Brisbane’s QPAC theatre in December this year.

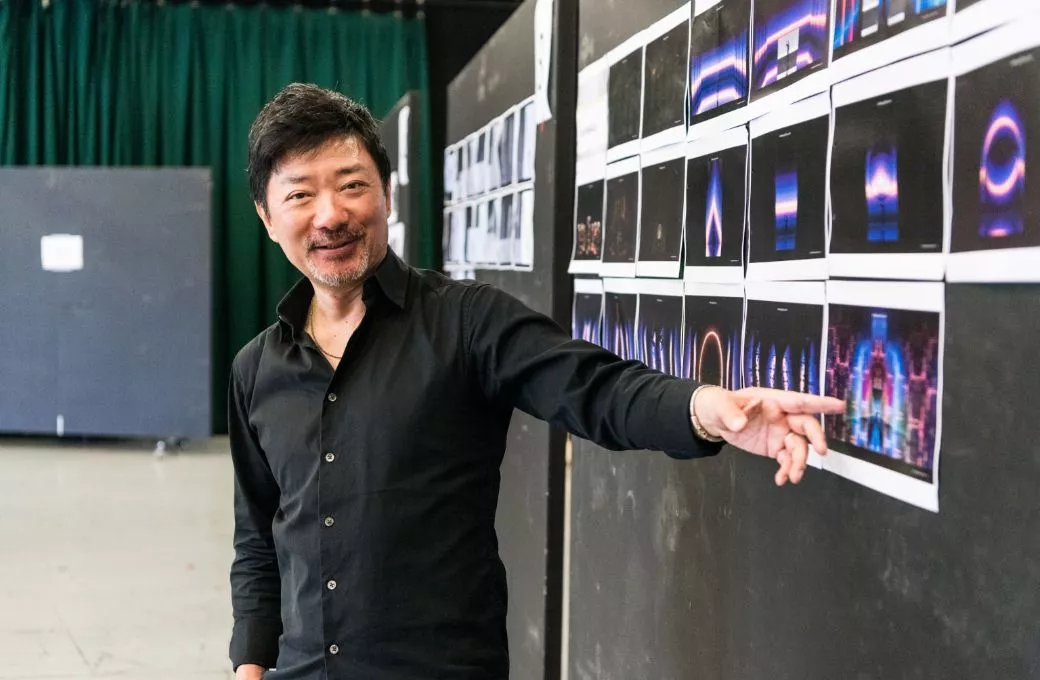

In the director’s seat is the versatile Chen Shi-Zheng (陈士争). China-born and New York-based, Chen boasts an eclectic portfolio of prestigious projects. He has directed everything from the Meryl Streep film Dark Matter, which won awards at the Sundance Film Festival, to the upbeat High School Musical: China.

In the opera world, Chen is perhaps best known for his lavish staging of The Peony Pavilion, an epic Chinese Kūn qǔ (崑曲) opera which he staged for the Lincoln Center Festival. Lasting almost twenty hours and featuring over 200 characters (and animals), The Peony Pavilion is bigger than the Ring cycle. “We called it the Ming Dynasty Ring, the Ming-Ring!” he jokes. “After that I thought ‘Oh well, they said this was longer than the Ring cycle so maybe sometime before I retire I should do the Ring.”

Chen’s first encounter with Wagner’s music had happened almost a decade before in New York. “It was just the beginning of my directing career,” he reminisces, “and I was trying to listen to different composers. There were still record stores back then! I was browsing in the classic CDs section, and I stumbled on this really old recording of Wagner’s music, from the sixties, a remastered CD. I listened to it periodically. I thought it was this unique, strange world.”

A few years later he saw Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde – “just divine”, he muses, “and then a friend of mine said to me, ‘When I die, I want the last aria from Tristan played at my funeral.’ And that revealed to me another layer of what Wagner’s music could mean for ordinary people.”

In keeping with this direct, straight-to-the-heart approach, Chen chose to be fresh and innovative for his own Der Ring des Nibelungen. His goal, he says, “was not to follow any kind of formula”. It’s a bold stance for an opera so steeped in tradition, including the ever-influential Bayreuth Festival productions.

“Of course,” Chen notes wryly, “I have friends who always tell me which periods had the best productions. You know – ‘you have to watch this one!’. Some you can find online, and some you can’t because they’re too old, but you can find photos. You get a sense of what those productions have achieved. But it’s been about 150 years since the operas premiered. And if you’re given an opportunity like this you really have to create your own form, one that’s more than just a minor adjustment to another production. Otherwise, you’re just wasting human resources and people’s money!” he laughs. “I kept trying to elevate myself to go further. In the Wagnerian world, it’s easy to fall into certain habits, to adopt certain formulas. So that became my goal: not to follow any formulas!”

After that, it was a matter of workshopping with the designers and singers. He held collaborative meetings in Berlin and Sydney, focused on identifying key visual reference points. “I kept trying to arrive at what I call a ‘Bible’,” he says, “a reference volume of photos, to build up a visual vocabulary. And then,” he grins, “we had to throw away every photo that looked too familiar.”

His brief from Opera Australia’s then-artistic director Lyndon Terracini was succinct: to create a Ring cycle that was digital, and Chinese. “I said, maybe Pacific instead,” Chen recalls, “you know, a little bit broader.

Was this difficult given the Ring is so deeply rooted in Germanic tradition? Chen’s response is open-minded. “I mean, it’s Wagner’s imagination. He wanted to bring Germanic mythology into the world of opera. And I thought we have to use this as a diving board. Take what Wagner has, then jump off into the unknown, into a world which reflects our existence. So that’s why it took a long time to find a vocabulary. This new Ring is not entirely West and it’s not entirely East. It’s a hybrid... It doesn’t follow either cultural tradition. It’s more like a mosaic, and I feel people will find many things they like.”

To capture the grandeur of Wagner’s world, Chen drew on futuristic space-travel. “You have to put Nature in it,” he explains. “But it’s not just our earthly nature, it’s the galaxy, the universe.”

There are several moments from his Ring that he identifies as personal favourites. “For the underwater home of the Rhinemaidens, I saw the coral in Queensland and thought it looked like Chinese tài hú (太湖石) stone. Tài hú is a lake rock, used in landscape gardening and for scholarly rock gardens. I thought it was an interesting way to think of the Rhinemaidens. In that scene, the three singers become aerial dancers, moving in and out of the coral water space, and it becomes a mixture of real and surreal moments, where you start to think this is a place you could enter to steal [the Rhinegold]. It creates this fantasy world.”

Another favourite scene features the three Norns who weave the Rope of Destiny. “I was really trying to find the right vocabulary to describe them,” he explains. “In the Prologue to Götterdämmerung, they’re almost telling the mythology’s pre-history. And then I was in this museum and found this African sculpture with a black metal rope as a skirt. I thought: when you tell stories about the past, what is passed on? What ends up being passed to us living today?” Chen describes storytelling in visceral terms: “I feel you almost pull out your heart, your guts – you sort of disgorge the entirety of your body. So when the Norns start talking, they start pulling material from their hearts and other parts of their bodies… All this internal colour starts pouring out. There’s about 15 or 20 minutes of this. It’s almost installation art!”

Chen becomes particularly animated describing a dragon he envisioned for Die Walküre, inspired by Indonesian jewellery. “Of course, we didn’t want to do another Chinese Dragon Dance! But I have this metal dragon bracelet I got from Indonesia. We made this metallic silver dragon – it’s huge! About sixteen meters! And I have a water soldier push this silver dragon to surround Brünnhilde’s rock. Then the soldiers light a fire so the dragon’s body is in flames – almost two feet of fire – and you see its body like a chain, or a bracelet, circling the rock with all this fire burning!”

Finally, there are the famous Valkyries, whom Chen has flying into the theatre space in futuristic aerial jets – although he cheerfully admits he hasn’t tried a joy ride himself as yet.

Chen is the first person of Asian descent to ever direct a Ring cycle. In explaining how this has impacted his thinking, he doesn’t focus on himself, or even the frequently-discussed need for diverse cultural representation in the arts. Instead, he optimistically explains the liberating effect this has had on his artistry. “As a director, I try not to be bound by tradition. Every artistic tradition has its own default, but because I’m coming from outside Western culture I feel like I have more freedom to roam around. I don’t have to confine my vision to any particular tradition or system, I actually have the freedom to create a bridge, to build a hybrid system. I can embrace or combine great elements from both systems… to create a third space, a meeting point, where great things can come together.”

He is philosophical about whether the Ring, with its obstinate gods, incestuous heroes, and ruthless mythical creatures, is “relatable” for modern audiences. “When you read headlines in the newspaper, they sound like something from a dramatic tragedy. I had a friend who used to say Greek tragedies show the disorganisation of human nature… Wagner showed that: this godlike desire and ambition to conquer, to destroy. I grew up during China’s Cultural Revolution: when I was very little I already found humans untrustworthy! With Wagner, the tragedy onstage exists in contradiction with the divine, beautiful sound of his music… It’s an artificial world, an organised story, but it still reflects our life.”

He hopes that the one thing audiences will take away from his Ring cycle is a shared sense of emotional mystery and ceremony. “Though I’m not Catholic, it’s the sort of feeling you get at a Catholic Mass – this shared emotional experience, this liturgy that’s a certain kind of awakening. In Chinese we call it a rebirth, niè pán (涅槃), a phoenix rising from the ashes. I feel the Ring cycle is just like that.”

Source: https://bachtrack.com/